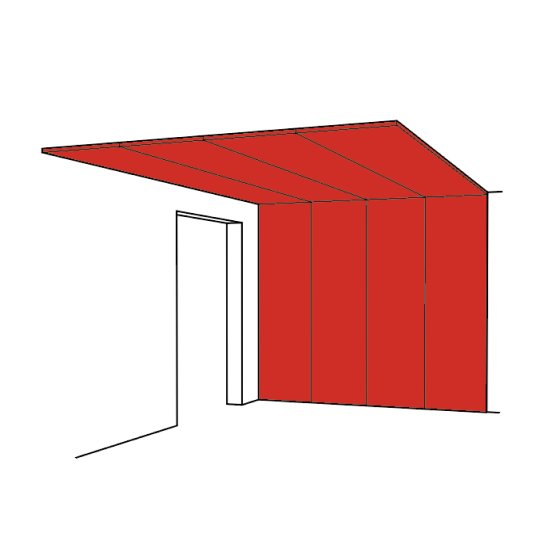

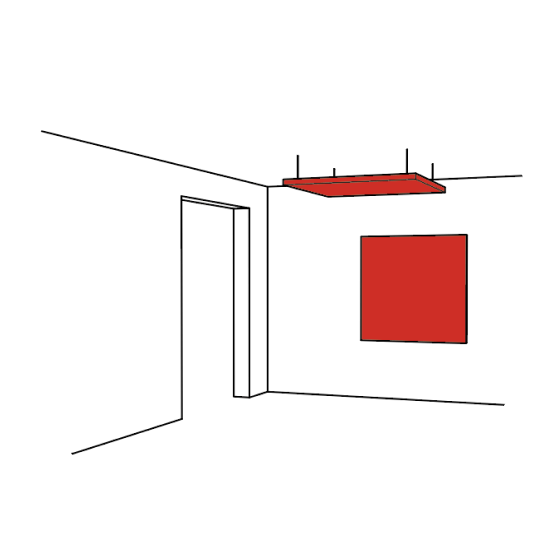

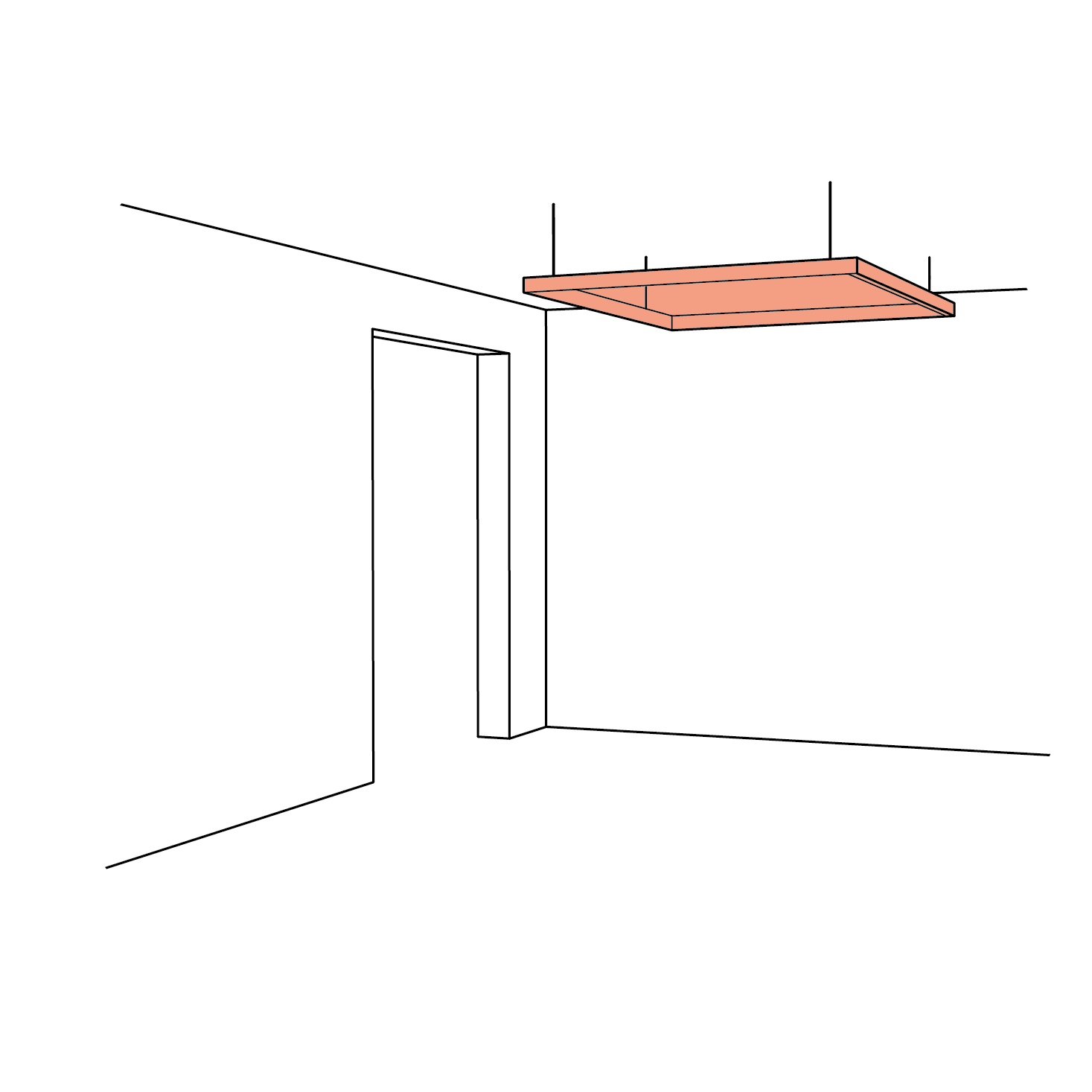

It all begins with a shared experience, that of visiting an empty flat and of finding it horribly echoing and resonant. And then of discovering that by filling it with furniture, curtains and living beings, it suddenly becomes a particularly comfortable, cosy and appeasing place to live… Let us not forget that textiles have long played a key role in interior design, through curtains, wall coverings and upholstery etc.

Textile and Architecture

1.

The words “textile” and “architecture” are ancient bedfellows, and each evokes the idea of elaborate, organic and complex structures… Take, for example, the expression “urban fabric.” Both are closely interwoven within the ancient civilisations of our world and their sonorities blend in meaningful echo—“texture” and “-tecture”—reminding us of their common function as a means of enclosing and covering. They imply both an intimate and collective dimension… German architect Gottfried Semper (1803–1879) presented the first analytical study of the etymology of architectural terms and what he refers to as the “textile origin of architecture.” “In German”, he writes, “the word decke at once refers to a “cover” and a “ceiling.” Zaun, or “fence”, shares an etymological origin with saum, a “seam” or “hem,” while gewand, meaning “garment” contains the word wand, meaning “wall…” 1. According to Semper, these terms are not mere metaphors, but the clear remnants of architecture’s origin in textiles. “It seems likely that the most ancient fabrics were inspired by roughly wreathed defensive barriers in prehistoric times”, writes Jacques Bril 2. “Textiles and stone masonry, weaving and architecture, have always played analogous, criss-crossing roles in our imaginary worlds and in the development of our technical know-how, as a means of enclosing the territory we inhabit and of providing shelter.” Textiles not only define architecture in the case of the yurt or tent. Our clothing, for instance, is our first real “home.” And think how tapestries were used to turn draughty castles into vastly more pleasant places to live. Both encase the body—textiles in an intimate, personal way and architecture at a slightly greater distance.

2.

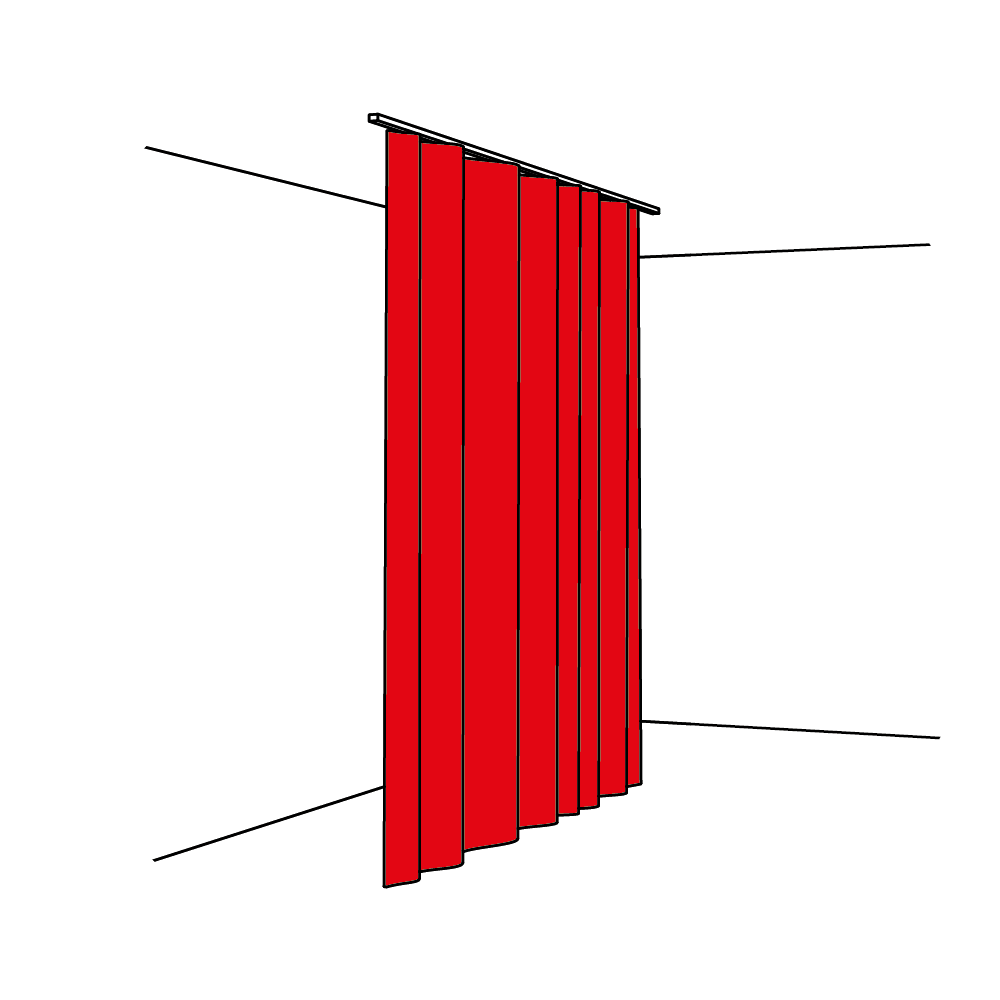

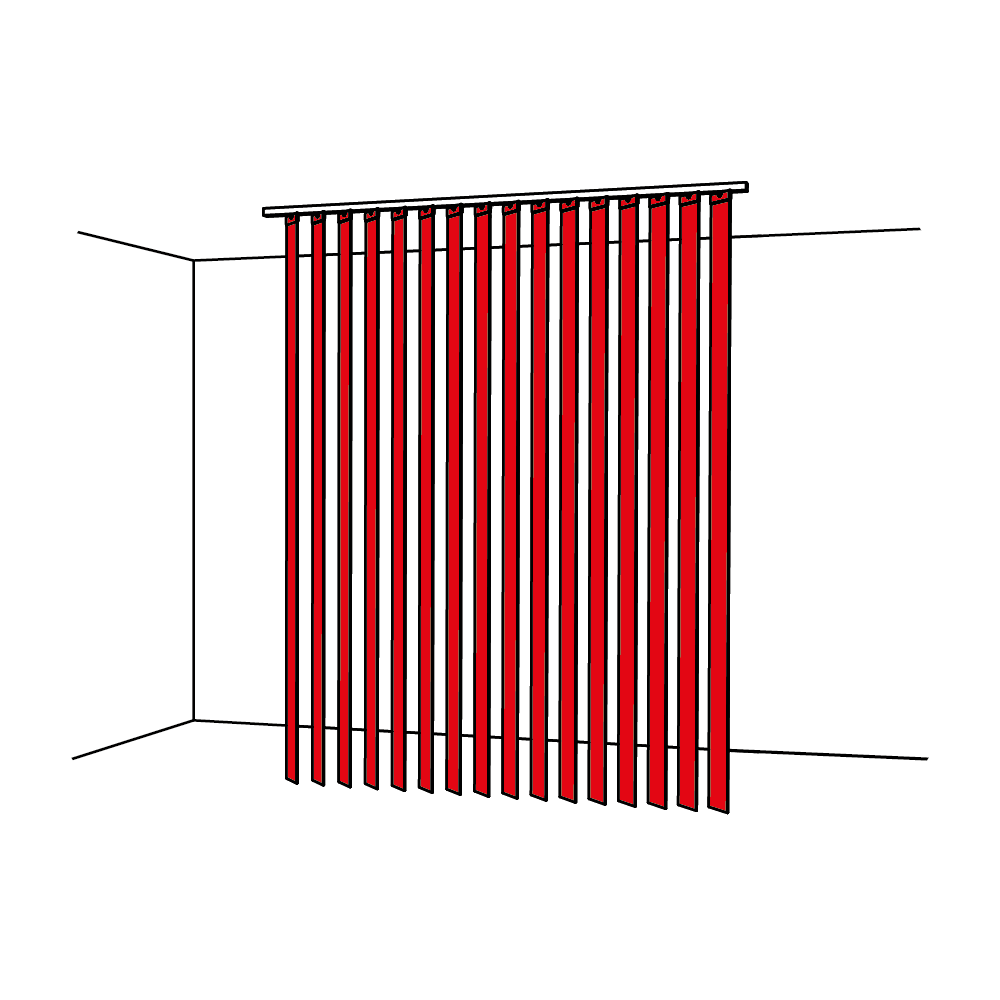

Not all modern architects have banned textiles from their designs, far from it. When, for example, one evokes the work of Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969), the pavilion built for the 1929 Universal Exhibition in Barcelona immediately leaps to mind. The building was clad in glass around an iron framework, stripped of superfluous detail but calling upon luxurious materials such as marble, travertine or red onyx in its execution. It is, without a doubt, one of modern architecture’s most emblematic creations. Yet people are less generally aware that Mies also built the Café Samt & Seide, or “Velvet and Silk Café”, for a fashion exhibition, Die Mode der Dame, held in Berlin in 1927. The café was designed in partnership with Lilly Reich and was planned as an open space, with subtly varying ambiances and individual areas delineated by a simple arrangement of velvet and silk panels of differing sizes and colours, suspended vertically like curtains from steel tubing. In this project, as in the later Barcelona pavilion, Mies explored not only the spatial qualities of the materials he was using, but also their interaction.

3.

“Architecture today is begging us to warm up its walls” wrote Le Corbusier (1887–1965) in an article singing the praises of tapestry. 3 “Tapestries are the nomadic mural of the modern man” he continues. “They can be taken with you, from one hotel room to the next, from one home to the next… All you have to do is roll one up under your arm, and, if you are off to the countryside for the weekend, you can hang it against a stone wall or some wood panelling… All at once it becomes a piece of clothing, making you feel nice and warm. Wool comes from the earth, from sheep. You can touch it, feel it, wash it…”

4.

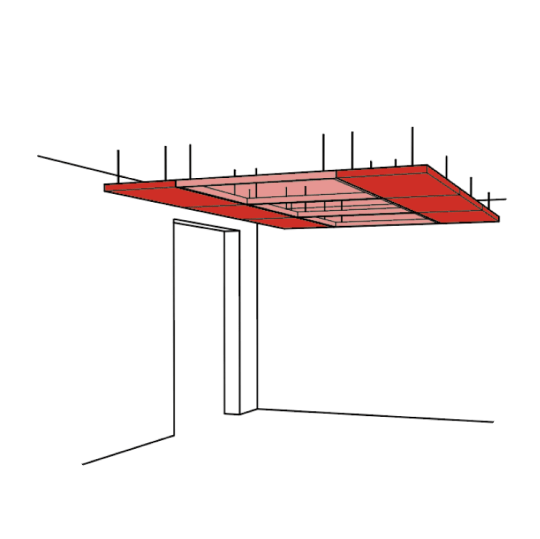

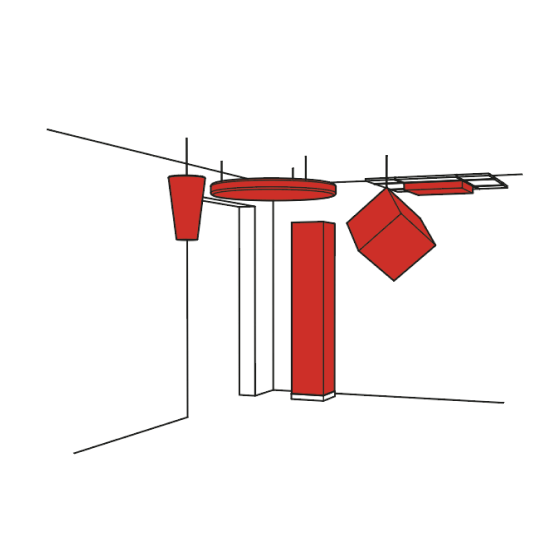

In the house Dutch architect Rem Koolhaas built in Floirac, near Bordeaux (1998), he inserted a complex system of runners into the ceiling of the split-level floor giving onto the garden. This allowed a variety of curtains, tapestries and voiles to slide open and shut. These “curtains” not only function as a filter, but also add a sense of intricacy and texture to the architecture through the bond they establish with the shifting weather and light, and this through their ambiguity and eccentricity. They may be extended outwards, enveloping the house to astonishing effect. They bring new spaces into being, their surfaces billowing and curling, wafting and lifting in the breeze, enticingly reminiscent of the Dance of the Seven Veils. In 2012, the curtains were revisited by artist Petra Blaisse, formerly invited by Rem Koolhaas to work on the Villa Dall’Ava (Saint-Cloud, 1991) and Casa da Música (Porto, 2005). Blaisse was invited to breathe new life into the house by introducing the exuberant curtains which are her hallmark. “The folds make a noise” she writes. 4 “The stuff that wraps our bodies and touches our skin becomes an element of architecture.”

5.

The contrasting sensations and impressions engendered by our environment spring not only from objective, quantifiable parameters linked with our activities, but also from more subjective phenomena, such as feelings, mood and cultural context. Our overall sense of comfort is born from the convergence of such diverse effects. Acoustic, visual or thermal comfort are, however, necessarily subjective notions, determined from an individual, personal perspective alone. Textiles are directly linked with the notion of what we define as a “comfortable atmosphere”—they are the ultimate “warm” materials, whereas steel or glass are considered to be essentially “cold.” Yet this impression is rooted in objective criteria which may be accurately measured—textiles have a low effusivity index. 5 Yet, as textiles have played an integral role in human existence for centuries, canvas, fabric, knitted materials and cloth have, over and above their obvious “absorbing” qualities, become “naturally” synonymous with comfort itself.

1. Gottfried Semper, Les quatre éléments de la construction, 1851

2. Jacques Bril, De la toile et du fil, éd. Clancier-Guénaud, 1984

3. Le Corbusier, « Tapisseries Muralnomad », in. Zodiac 7, Milan, 1960

4. Petra Blaisse, Inside Outside, MAI publisher, 2009

5. Effusivity. When you walk barefoot in the bathroom, the bath mat feels much warmer than the ceramic tiling. Both are actually at the same temperature, i.e. air temperature. This curious phenomenon is caused by the fact that each material warms up at a different speed due to their differing effusivity index— the lower the index, the quicker the material warms up. Thermal effusivity, also sometimes referred to as “subjective heat”, therefore describes the capacity of a given material to transfer heat when brought into contact with another material. It is also a means of describing the “hot” or “cold” sensation different materials produce.

How can I get a quote?

By contacting the Texaa business representative of your region by telephone or e-mail and leaving your contact details and what you need. We will send you a quote promptly.

How can I order Texaa products?

Our products are manufactured in our workshop and made available to order. Just contact the Texaa business representative of your region. If you already have a quote, you can also contact the person handling your order: the name is at the top left of your quote.

How do I get my products installed?

Joiners and upholsterers are the best skilled to install our products easily. We work regularly with some professionals, who we can recommend. If you have a tradesperson, who you trust, we can support him/her. You can find our installation instructions and tips here.

Got a technical question?

All our technical data sheets are here. Your regional Texaa business representative can also help; please feel free to contact him/her.

Can I have an appointment?

Our business representatives travel every day to installation sites and to see our customers. Please feel free to contact them and suggest the best dates and times for you, preferably by e-mail.

Lead times

Our products are manufactured to order. Our standard manufacturing time is 3 weeks for most of our products. Non-standard products take from 5 weeks. We also perform miracles on a regular basis! Please feel free to contact us.

Who should I call?

To get a quote, a delivery time or technical information, we recommend you call your regional Texaa business representative, who you can find here.

Order tracking

If you need information about your order, please contact the person in charge of handling it: the name is at the top left of your quote.