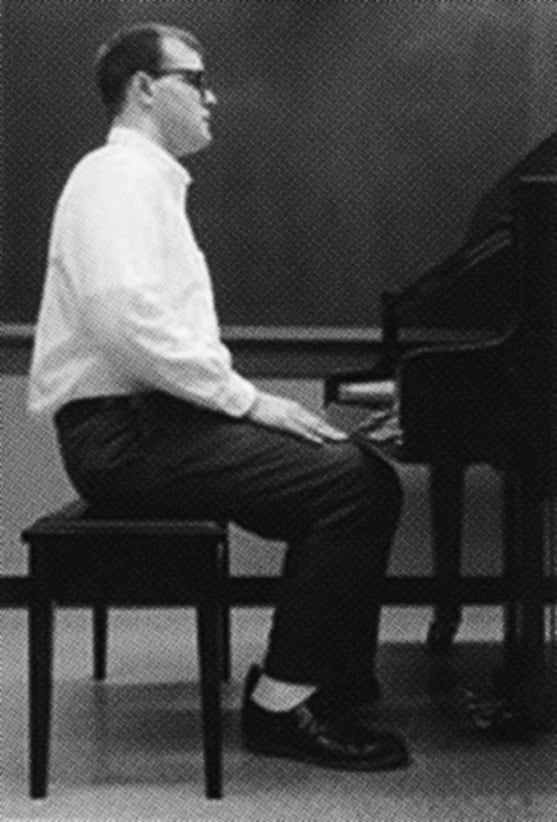

The programme for a concert given on 29th August 1952 at Maverick Concert Hall in Woodstock, New York, announced that a piece of contemporary music for the piano was to be performed. And indeed, as one might have anticipated, the audience waited eagerly as the pianist settled down, adjusted his piano stool and unfolded his score. Only to then close the lid of the keyboard. Thirty-three seconds ticked by before pianist David Tudor once again lifted the lid.2 Not a single note had been played, but the first movement was already over… It was time for the second movement, and then the third.

“Silence is a real sound…”

John Cage, 1952

The sound of silence

The audience present that night was the first to enjoy a performance of 4’ 33”—a piece often described as “four minutes and thirty three seconds of silence.” John Cage’s composition is considered today as a milestone in the history of music. “Over and above the aplomb of David Thomas’s performance, 4’ 33” throws our whole conception of music into question and is the work of a composer intent on making us ‘listen’ in a totally new way. How could silence be transformed into music? And, more essentially, how could it become the foundation on which our relationship with music is based.” 3

Learning to listen

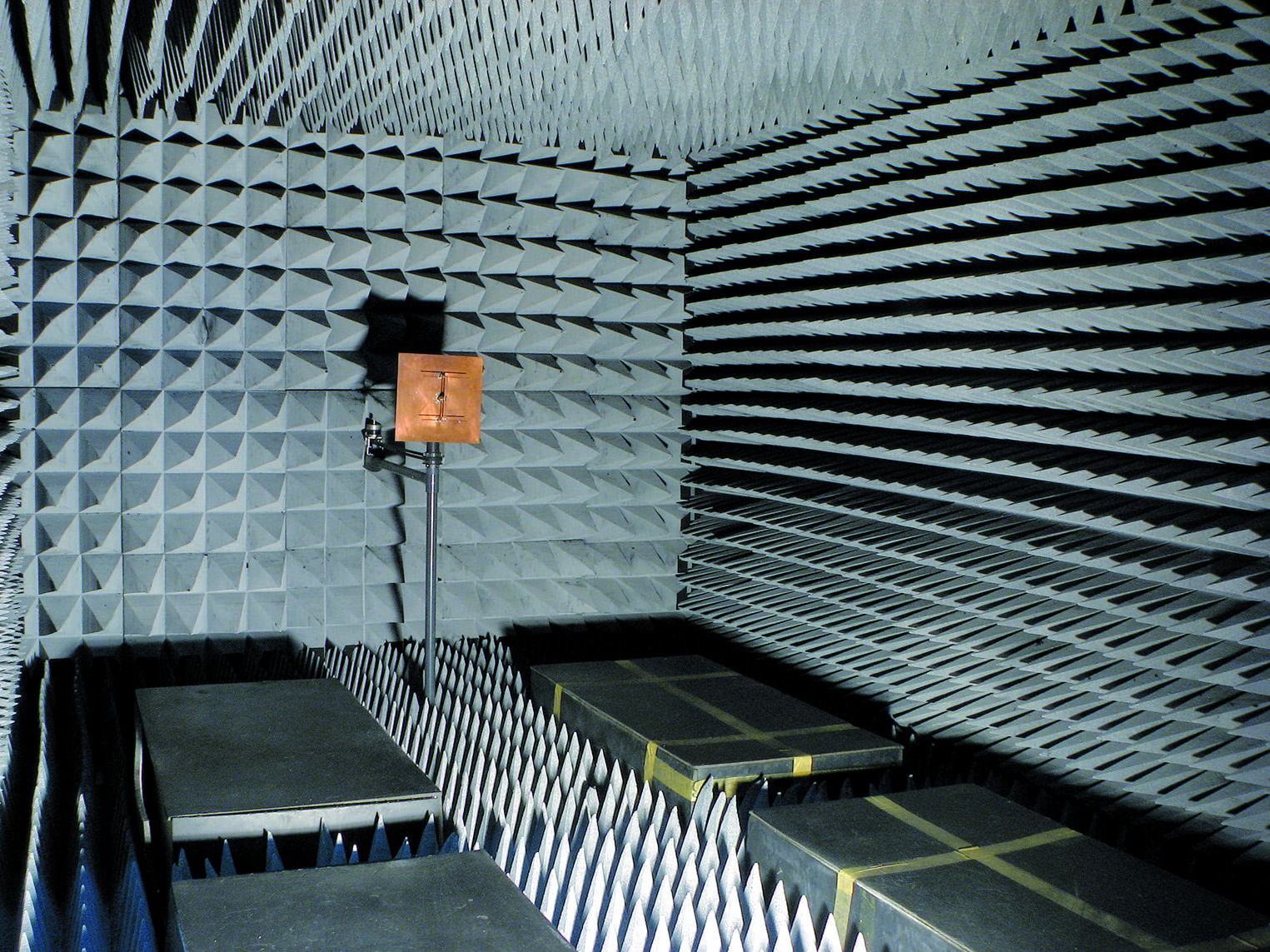

As an offshoot of technical research carried out in the industrial era, the idea for 4’ 33” was born in an anti-echo chamber 4 at the University of Harvard. Astonished that he could still hear sounds in such an ultra-silent, perfectly insulated environment, John Cage soon realised that he himself was their source. Two sounds persisted, despite the pervading silence. The first was high-pitched, the second much lower. They were nothing other than his heartbeat and the workings of his nervous system. This led him to the discovery of an undeniably blatant fact—silence does not exist. The experiment reinforced his convictions as to the musical value of the sounds of everyday life, produced without the least melodic intention. “Silence is a real sound.”

In his impossible quest for silence, John Cage forfeited his role as composer and instead began to concentrate on guiding his listeners’ ears. He rejoiced in the sense of loss thereby engendered. “There is poetry as soon as we realize we possess nothing”, he says quite simply. Life is a constant crackling and rustling, and the impossibility of silence turns traditional roles upside down. Cage exploits the context of performance to lead the spectator off the beaten track, subverting our expectations and forcing us to take centre stage in the music itself. Intimately linked with both the place and time of performance, born from the audience’s own attentive ears, 4’33” is an experimental dialogue, an invention from which each and every listener reaps fruit. The sound of breathing and whispering, the murmur of the wind or rustling of the audience are all instruments in this unique symphony. “The audience becomes the artist, but what of the composer—what does he become? He becomes a listener and lends his ear.”

A radical new stance

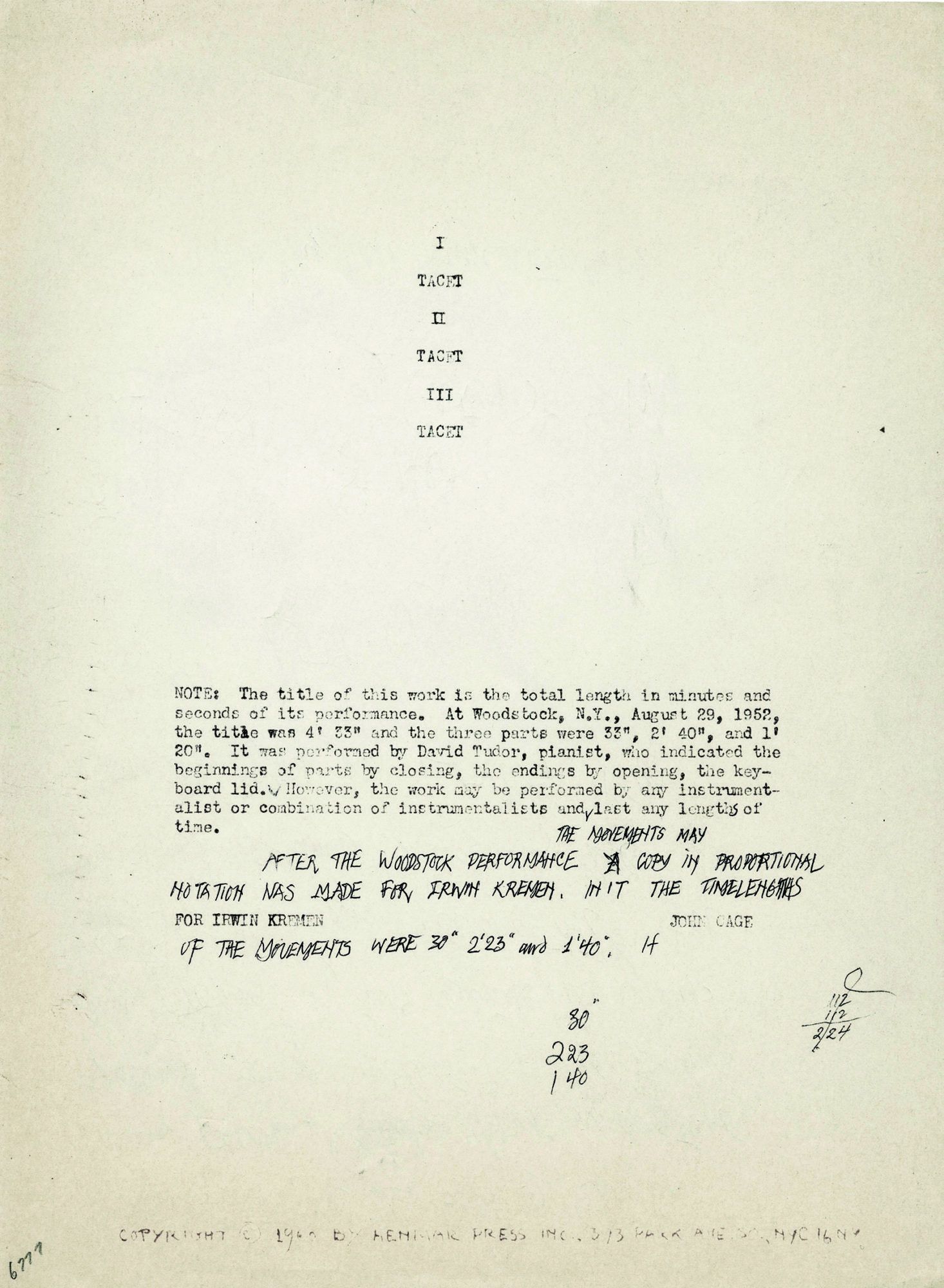

4’ 33” is a living piece of music, taking the musician to the very limits of artistic performance and entirely dependent on the recitalist’s behaviour. In a note appending the score published after the first performance 5, John Cage lists the piece’s three movements as lasting 30”, 2’ 23” and 1’ 40” respectively. He goes on to add that the piece may be performed by “any instrumentalist or combination of instrumentalists” and may “last any length of time.” The piece was therefore destined to an eventful existence, with each new performance regenerating it anew.

It also provided John Cage with the means of transposing ideas issuing from contemporary research in the plastic arts to the field of music.

His inspiration came from the work of one of his painter friends, Robert Rauschenberg, who had produced a series of white paintings. Although at first sight totally devoid of content, the tones of the canvases in question shift in accordance with the luminosity of the room in which they hang, or in relation to shadows projected onto them by onlookers. Yet 4’ 33” also cocks a snook at the music industry, in that it adopts the standard formula of the pop song (“Four minutes and thirty-five seconds of bliss…”). It functions as the degree zero of music, thereby defining new foundations. The piece’s total duration (273”) has also been interpreted as a measurement of temperature. What we refer to as absolute zero—0° Kelvin—is indeed equal to –273.15°C.

Others argue that 4’ 33” is in fact a ready-made, in the style of Marcel Duchamp. John Cage was living in France when he composed the work, and on the azerty keyboard of his typewriter, the figure 4 corresponds to a ’ sign, and the figure 3 to ”…

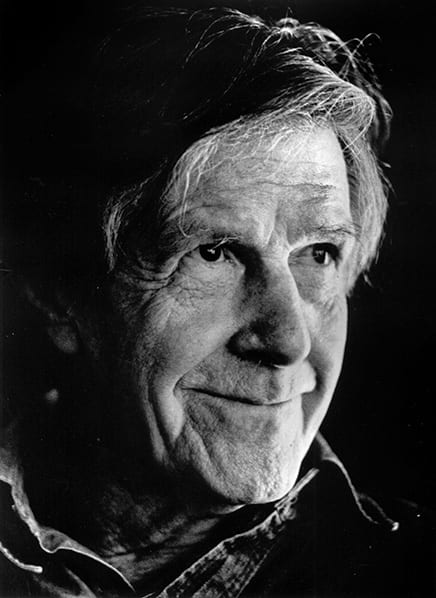

1. John Cage (1912 –1992)

Compositeur, poète, théoricien, plasticien et écrivain. Tout son travail vise à la relativisation de la personnalité de l’auteur et au refus d’établir une distinction entre vie et art. C’est la source, dans son œuvre, de l’utilisation du hasard qui émancipe la musique de la mémoire et de l’intention, et de l’absence de hiérarchie entre les sons musicaux et les autres. En témoignent, dès le début des années 1940, l’utilisation de sons produits électriquement, et des pièces telles que 4’ 33” où le son ambiant de la salle de concert est toute la substance de l’œuvre.

2. David Tudor (1926 –1996)

Pianiste et compositeur de musique expérimentale. Il assure la création américaine de la Sonate pour piano nº 2 de Pierre Boulez

en 1950. Karlheinz Stockhausen lui dédie son Klavierstück VI (1955). Son nom est surtout associé à celui de John Cage pour qui il a créé Music of Changes, le Concerto pour piano & orchestre et le célèbre 4’ 33”.

3. Guillaume Benoît, in. Evene.fr

4. Une chambre anéchoïque (ou chambre sourde) est une salle d’expérimentation dont les parois absorbent les ondes sonores. On utilise de telles chambres pour mesurer des ondes acoustiques en l’absence de composantes ayant subi une réverbération sur des parois, par exemple, pour caractériser la directivité ou la sensibilité d’un microphone, ou la bande passante d’un haut-parleur, d’une enceinte acoustique, etc.

5. « Le titre de cette œuvre figure la durée totale de son exécution en minutes et secondes. À Woodstock, New York, le 29 août 1952, le titre était 4’ 33” et les trois parties 33”, 2’ 40” et 1’ 20”. Elle fut exécutée par David Tudor, pianiste, qui signala les débuts des parties en fermant le couvercle du clavier, et leurs fins en l’ouvrant. L’œuvre peut cependant être exécutée par n’importe quel instrumentiste ou combinaison d’instrumentistes et sur n’importe quelle durée. »

Are our products fire-resistant?

Yes, our products are fire-resistant and comply with regulations governing public-access buildings.

Texaa solutions are tested for reaction to fire in accordance with international standards. Fire reaction test reports (fire certificates) are available upon request to support specification.

Please feel free to contact us by email at cf@texaa.co.uk or by phone at +44 (0) 20 7092 3435.

How can I get a quote?

By contacting the Texaa business representative of your region by telephone or e-mail and leaving your contact details and what you need. We will send you a quote promptly.

How can I order Texaa products?

Our products are manufactured in our workshop and made available to order. Just contact the Texaa business representative of your region. If you already have a quote, you can also contact the person handling your order: the name is at the top left of your quote.

How do I get my products installed?

Joiners and upholsterers are the best skilled to install our products easily. We work regularly with some professionals, who we can recommend. If you have a tradesperson, who you trust, we can support him/her. You can find our installation instructions and tips here.

Got a technical question?

All our technical data sheets are here. Your regional Texaa business representative can also help; please feel free to contact him/her.

Can I have an appointment?

Our business representatives travel every day to installation sites and to see our customers. Please feel free to contact them and suggest the best dates and times for you, preferably by e-mail.

Lead times

Our products are manufactured to order. Our standard manufacturing time is 3 weeks for most of our products. Non-standard products take from 5 weeks. We also perform miracles on a regular basis! Please feel free to contact us.

Who should I call?

To get a quote, a delivery time or technical information, we recommend you call your regional Texaa business representative, who you can find here.

Order tracking

If you need information about your order, please contact the person in charge of handling it: the name is at the top left of your quote.