The interior design of the ‘Aubette’ building in Strasbourg is often referred to as the Sistine Chapel of abstract avant-garde art between the wars. The work was completed in 1928 by Theo van Doesburg, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hans Arp, and pays eloquent witness to the endeavours of Modernist artists working in this period to marry colour with architecture.

L’Aubette

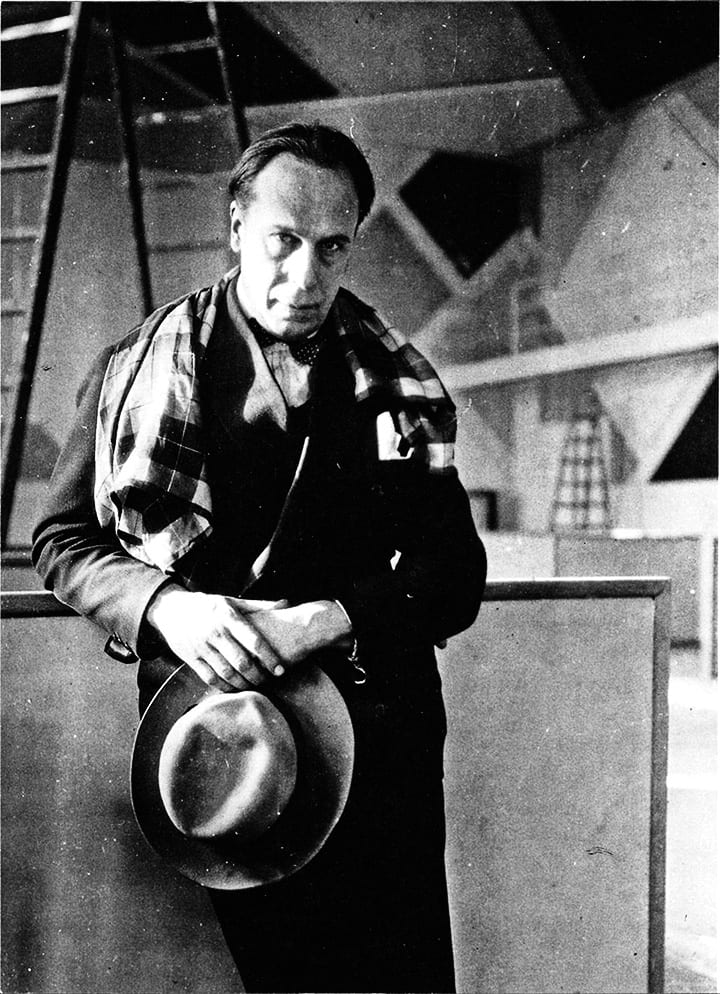

Theo van Doesburg,

Strasbourg, 1928

‘The point is to situate man within painting, rather than in front of it.’

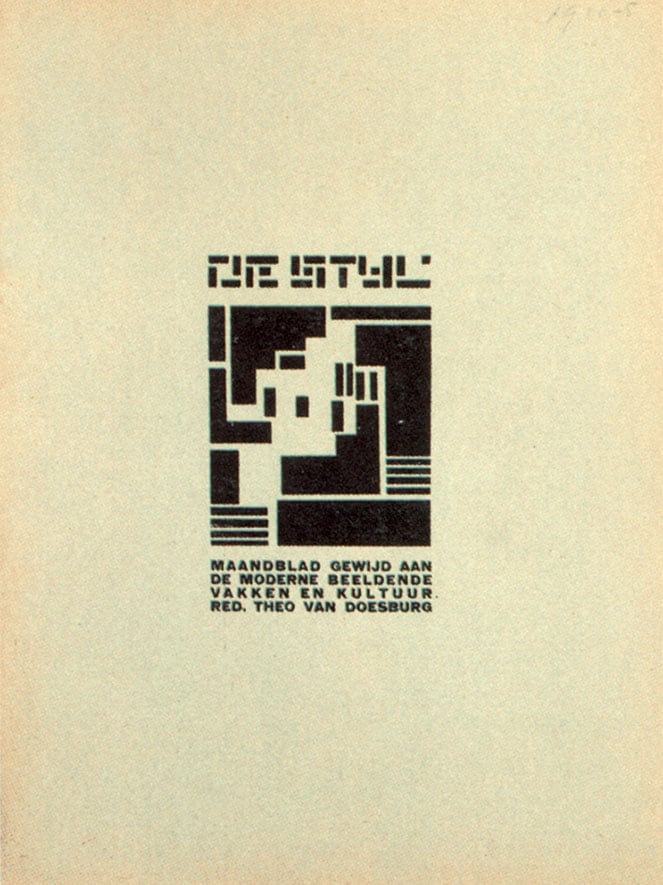

Theo van Doesburg (Utrecht 1883–Davos 1931) was a painter, poet and art theoretician. In 1917, he founded the review De Stijl with Piet Mondrian, as a means of disseminating their ideas on aesthetic principles they referred to as Neo-Plasticism—geometric shapes, an absence of curves or diagonal lines, exclusive use of primary colours, specifically blue, red and yellow, in association with non-colours, like grey, black and white.

In the early 1920s, van Doesburg temporarily gave up painting to devote himself to architecture, and more explicitly the role played by colour in building design. He worked on projects in partnership with J.-J.-P. Oud in Rotterdam, including houses in Spangen (1921) and the house of the site manager of the Cité Oud-Mathenesse (1923). He then went on to work with Cornelis van Eesteren on an ambitious project for a university building in Amsterdam (1923), never built but providing van Doesburg with the opportunity of putting his theories into practice at the drawing board.

‘We have given colour its true place in architecture’ he wrote in 1924, ‘and we declare that painting which is separate from architectural construction (that is, easel painting) has no raison d’être.’ 1

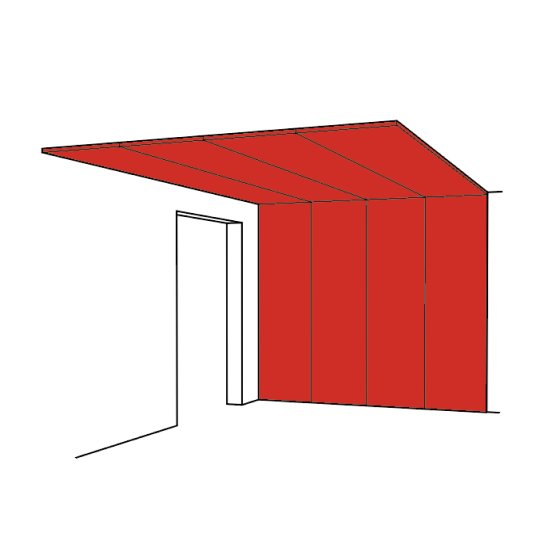

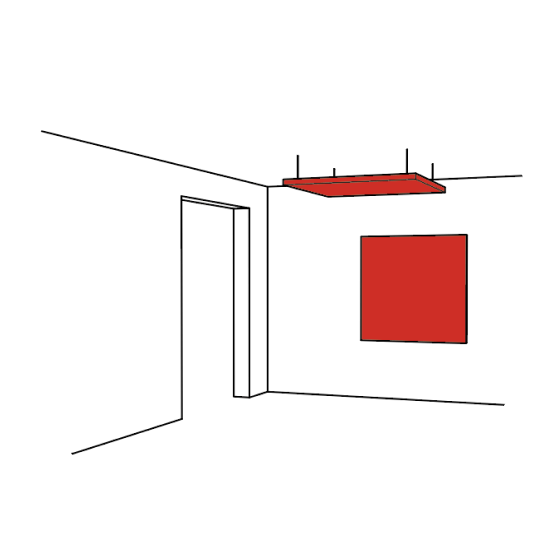

For Theo van Doesburg, colour is not, then, a mere component of interior design, but rather a spatial element in creation. ‘For new architecture, colour is incredibly important; it is a means of expression. It is thanks to colour that the volume relations sought by the architect become visible; colour completes architecture; colour is an essential element of architecture. […] It is the very material of expression, equal in value to other materials, such as stone, iron or glass.’ 2

Strasbourg

In the early 1920s, two brothers, Paul and André Horn—one an architect, the other a chemist—set up a real estate company together in Strasbourg and began working on a number of urban redevelopment projects. They took out a lease on the right wing of ‘L’Aubette’, a building on the corner of Place Klébert and erected in the 18th century by the military. Their plan was to redevelop the building as a place for dining and entertainment. Paul came up with an initial design for its internal reorganisation, but the brothers soon decided to call upon the services of two artists, Sophie Taeuber-Arp and Hans Arp, for the interior design. The artists in turn invited Theo van Doesburg to join them, and he seized upon their offer as a means of putting the ‘synthesis of art’ advocated by De Stijl into practice. The ‘synthesis of all arts’ was a universal art form based on the effacement of individuality in artistic practice in favour of collective work. ‘Messrs Horn have invited me to Strasbourg’ writes van Doesburg, in a special issue of the review De Stijl in 1928 ‘and this has provided me with the opportunity of putting my ideas on interior design into practice on a large scale, by giving the finest rooms a Modernist make-over.’ 3

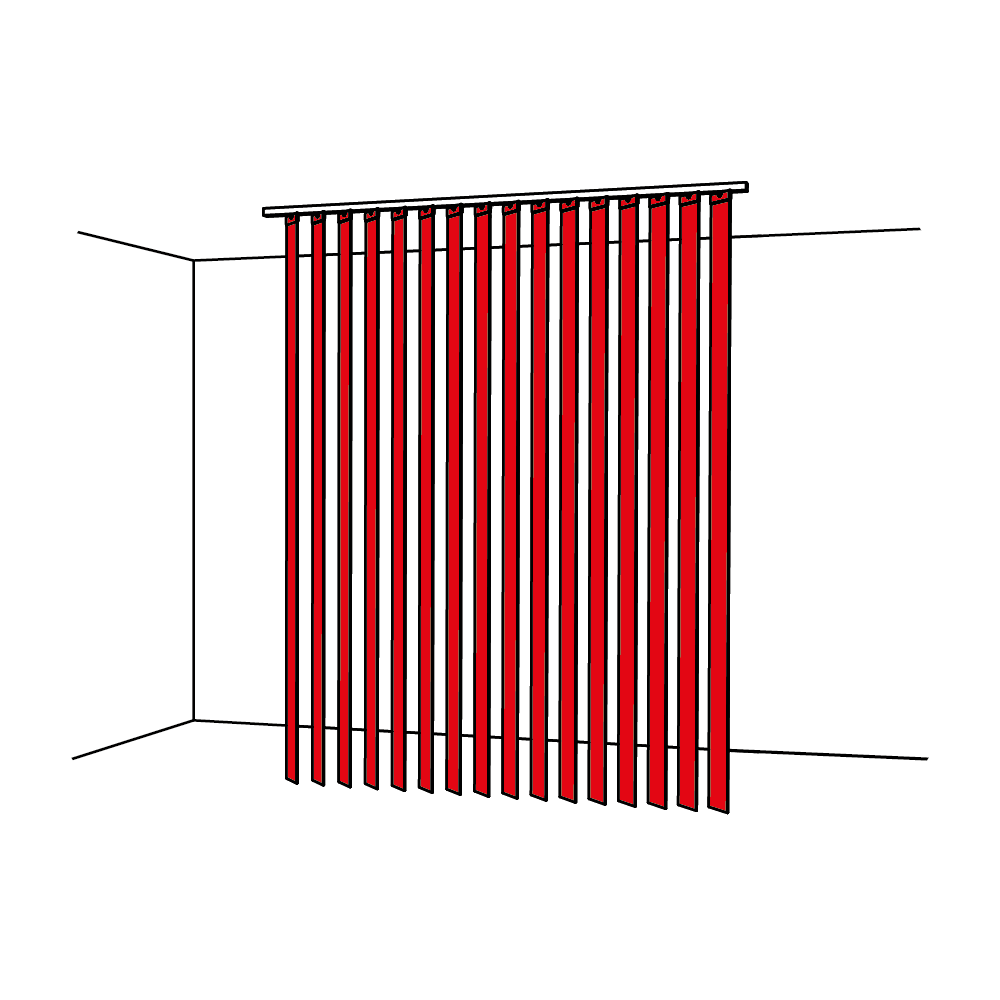

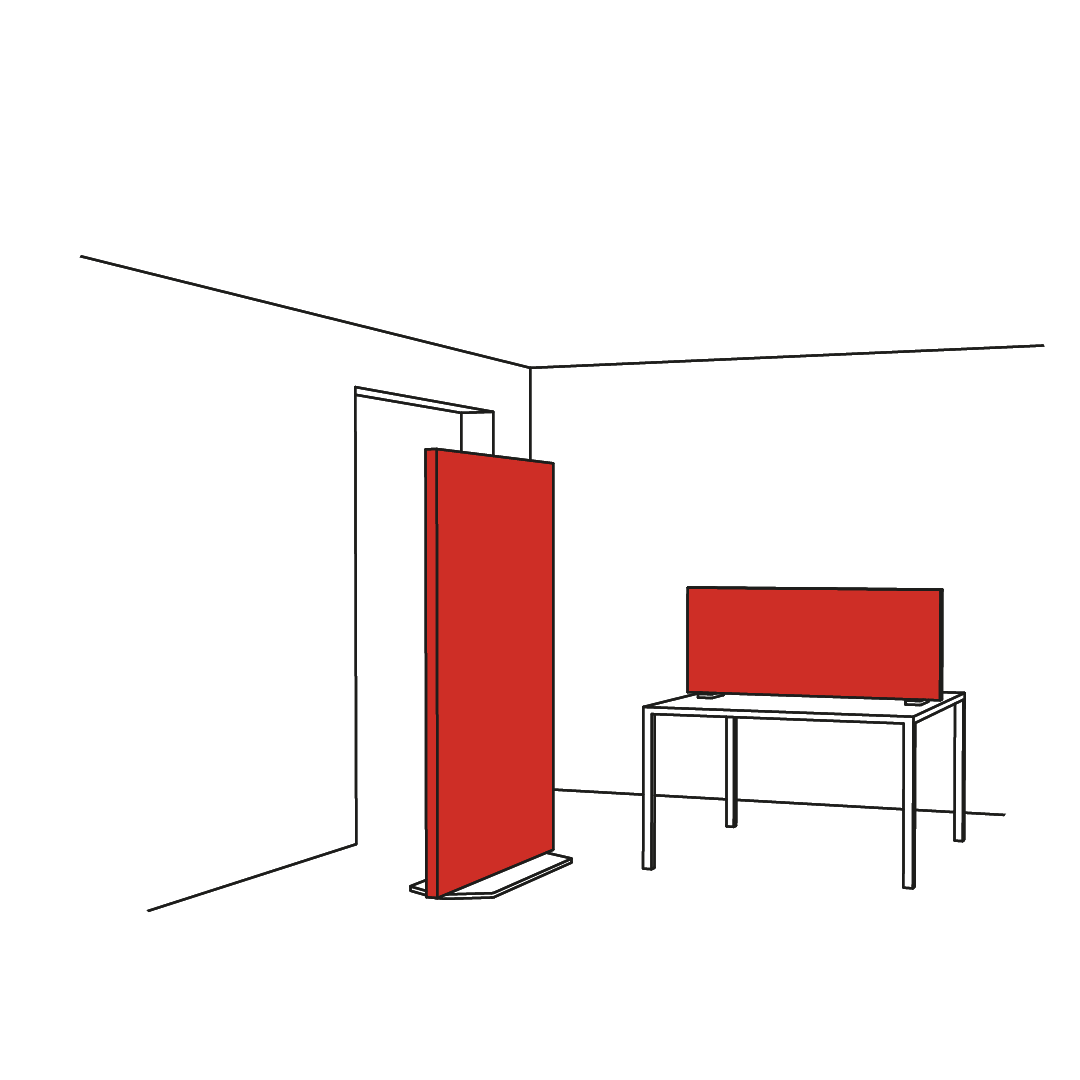

The three artists invested the different spaces available to them each in their own way, with Theo van Doesburg in charge of the overall project management and publicity. ‘As we were working together as co-directors on this project, we laid down the principle that each individual would be free to work according to his own ideas.’ 4 When L’Aubette opened as a place of entertainment in 1928, its facilities were distributed over four floors. In the basement was the American bar and vaulted dance hall, designed by Hans Arp. On the ground floor, the Café-Brasserie and restaurant owed their interior design to Theo van Doesburg, while Sophie Taeuber-Arp took responsibility for the Five-O’Clock tearooms and L’Aubette-Bar. The lavatories, cloakrooms and billiard hall, designed by Hans Arp, were positioned on the mezzanine floor. The first floor also accommodated the Cinema–Dance Hall and Function Room designed by Theo van Doesburg, while the adjoining Foyer-Bar was designed by Sophie Taeuber-Arp.

The Cinema–Dance Hall

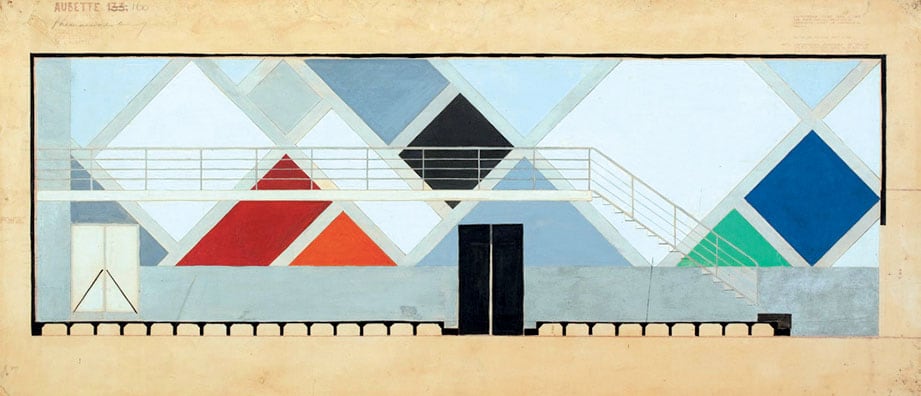

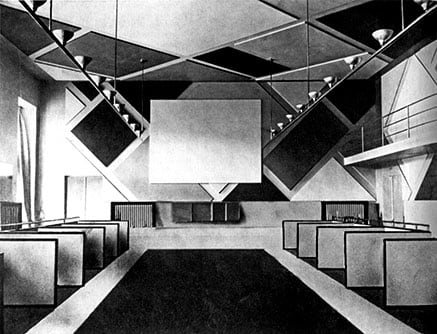

The layout of the hall, with its staircase and rectangular projection screen, inspired Theo van Doesburg to unfold a diagonal grid pattern of squares, rectangles and triangles in black, white, yellow, green, blue and red, across the walls and ceiling. ‘As the architectonic elements are based on an orthogonal relationship, the distribution of colours in this room had to be treated diagonally, as a counter-composition, in such a way as to withstand the architectural tension. […] If one were to ask me what I had in mind as I was designing this room, I might well answer—opposing the three-dimensional nature of the material room with a pictorial, sur-material diagonal space.’ 5 This affirmation of the diagonal line throws into question the aesthetic theories of Piet Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism, which advocated the sole use of vertical and horizontal lines.

Function Room

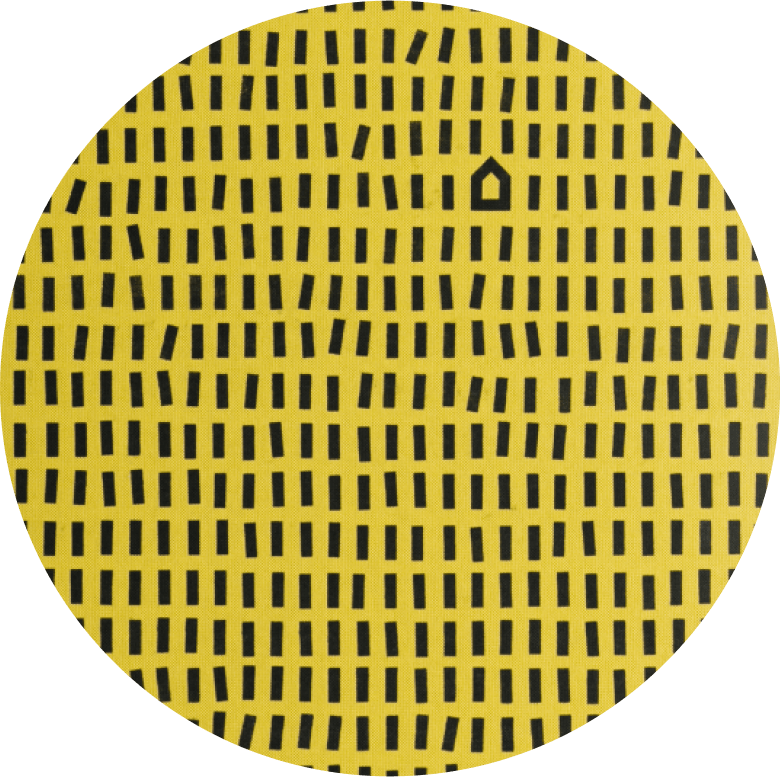

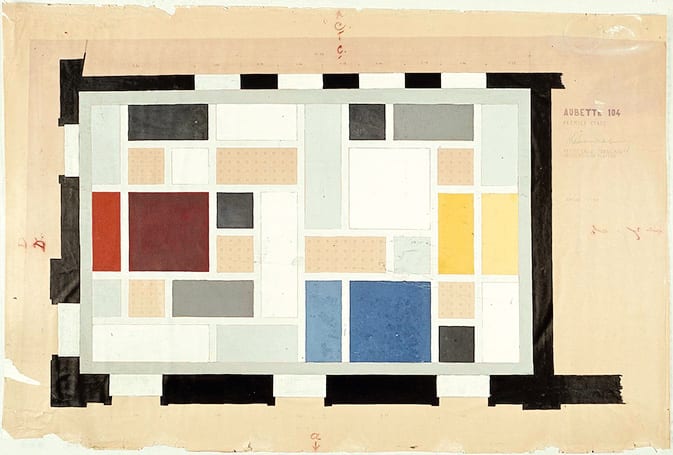

Here Theo van Doesburg uses an exclusively orthogonal design based on a series of squares. The chromatic palette is made up of primary colours (yellow, blue and red), along with the non-colours (black and white) dear to the heart of Neo-Plasticism. Two shades of the same colour are set side by side here to create a form of dissonance. ‘As for the distribution, I used standard measures. The smallest coloured surface measures 1m20 x 1m20, while the larger areas are always a multiple of 1m20 x 1m20, plus the width of the band (30 cm).’ 6

Foyer-Bar

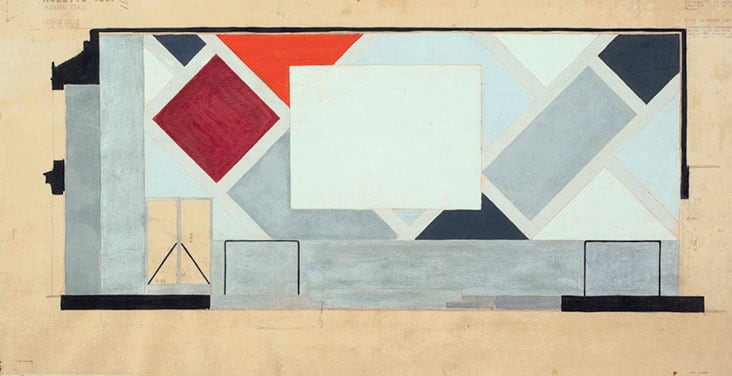

Designed by Theo van Doesburg to link the Function Room with the Cinema-Dance Hall, the Foyer-Bar enabled visitors to watch a film while still being able to move around. Sophie Taeuber-Arp was the inspiration behind the rectangular blocks of red, grey, light grey and white, across the walls and ceiling. The floor is treated similarly.

L ’Aubette, 1928

Unfortunately, the original interior décor of L’Aubette remained in place for less than ten years. When the Horn brothers withdrew from the venture in 1938, their successor decided to revamp the interior, thereby effacing the avant-gardist décor of the original which had never truly conquered the hearts of the Strasburgers.

For years to come, little more was known of L’Aubette than what could be seen in a handful of black and white photographs. And yet the Cinema-Dance Hall, with its colourful diagonal grid pattern and suspended gallery, had become a key aesthetic symbol of the period and a historical icon of the bonds linking architecture to colour. The original painted panels were rediscovered quite by chance in the 1970s and were awarded heritage protection in 1985 and 1989. Restoration work was undertaken in 1985 and completed in 2006.

Today, the first floor of L’Aubette has been returned to its former glory and is open to the public, providing us all with the opportunity of ‘situating ourselves within the painting, rather than in front of it’, in the words of Theo van Doesburg. In doing so it becomes quite clear that the effect produced by this interior by far surpasses the limits of mere decoration. Elementary forms, straight lines and three colours, together with black, grey and white, suffice to turn a colourful composition into a monumental tour de force, literally shaping the space and atmosphere of each room. This is clearly a ‘complete’ work of art.

—

For further information: www.musées.strasbourg.eu

On the Meaning of Colour in Architecture

by Theo van Doesburg

‘It is important to establish a clear distinction between the three main trends in architecture, as this plays a crucial role in how colour is used.

1. Decorative architecture.

2. Constructive, exclusively utilitarian architecture.

3. Plastic architecture.

In decorative architecture, colour is used as a means of decorating the surfaces created by the architectural design. Its use here is exclusively ornamental and in no way does the colour become one with the architecture. It remains an independent element which, instead of giving the building greater strength, does little more than camouflage it, or, in the most extreme cases, destroy it (as in the Baroque period). In constructive architecture, designed purely as a response to material needs, colour, in the form of some absolutely neutral shade such as grey, green or brown, serves no other purpose than to underline the element used to link and unify the architectural design, or protect the wood, ironwork etc. against the elements. As a result, colour merely accentuates the constructive, anatomical character of architecture of this type. Utilitarian architecture only takes the practical side of life into account; the functional mechanics of life, of where we live or work. However, a higher necessity, above and beyond these purely practical considerations, does exist, a necessity of a spiritual order. If the architect or engineer wishes to make the balance of a given building’s proportions visible, in other words, express how a wall functions in relation to space, their intentions are no longer exclusively constructive, but also plastic. As soon as the wall is made visible, and its relation with other elements in the building’s construction highlighted, including its relation with the materials used, then the aesthetic dimension of the design is brought into play. Consciously voicing this balance of relations is synonymous with producing a plastic work of art. At this stage, a stage we might call the ‘stage of plastic architecture’, colour becomes the matter through which such ideas are voiced, just like the other materials used, such as stone, ironwork or glass. In this case, colour is not just a means of orientating the design, in other words of making visible such elements as distance, position or the angle of volumes and objects, but is first and foremost a means of satisfying the desire to make visible the mutual relationship between spaces and objects, between direction and position, or measure and direction etc. The aesthetic role of architecture resides in how these proportions are ordered. If harmony is reached through this process, then so too is style. No further demonstration is necessary; a balance may only be reached through a close working partnership between engineer, architect and painter. At this stage, architecture has surpassed its purely constructive phase, and has attained a higher level of refinement. No longer satisfied with merely exhibiting its anatomy, it has become an animated and inseparable body.’

—

Taken from La Cité: Urbanisme, Architecture, Art Public, vol. 4, # 10, Brussels, May 1924

1. Doesburg / Eesteren, 1923 –1924, cité par Mathias Nosil,

« Peindre l’espace », in L’Aubette ou la couleur dans l’architecture, Strasbourg, 2008

2. Theo van Doesburg,

« La signification de la couleur en architecture », in La Cité : urbanisme, architecture, art public, vol. 4, # 10, Bruxelles, mai 1924

3. Theo van Doesburg, « Notices

sur l’Aubette à Strasbourg »,

in De Stijl # 8 (1928) nr. 87- 89, Aubette, Strasbourg

http://fr.wikisource.org/wiki/Notices_sur_l’Aubette_à_Strasbourg

4. id.

5. id.

6. id.

7. id.

Are our products fire-resistant?

Yes, our products are fire-resistant and comply with regulations governing public-access buildings.

Texaa solutions are tested for reaction to fire in accordance with international standards. Fire reaction test reports (fire certificates) are available upon request to support specification.

Please feel free to contact us by email at cf@texaa.co.uk or by phone at +44 (0) 20 7092 3435.

How can I get a quote?

By contacting the Texaa business representative of your region by telephone or e-mail and leaving your contact details and what you need. We will send you a quote promptly.

How can I order Texaa products?

Our products are manufactured in our workshop and made available to order. Just contact the Texaa business representative of your region. If you already have a quote, you can also contact the person handling your order: the name is at the top left of your quote.

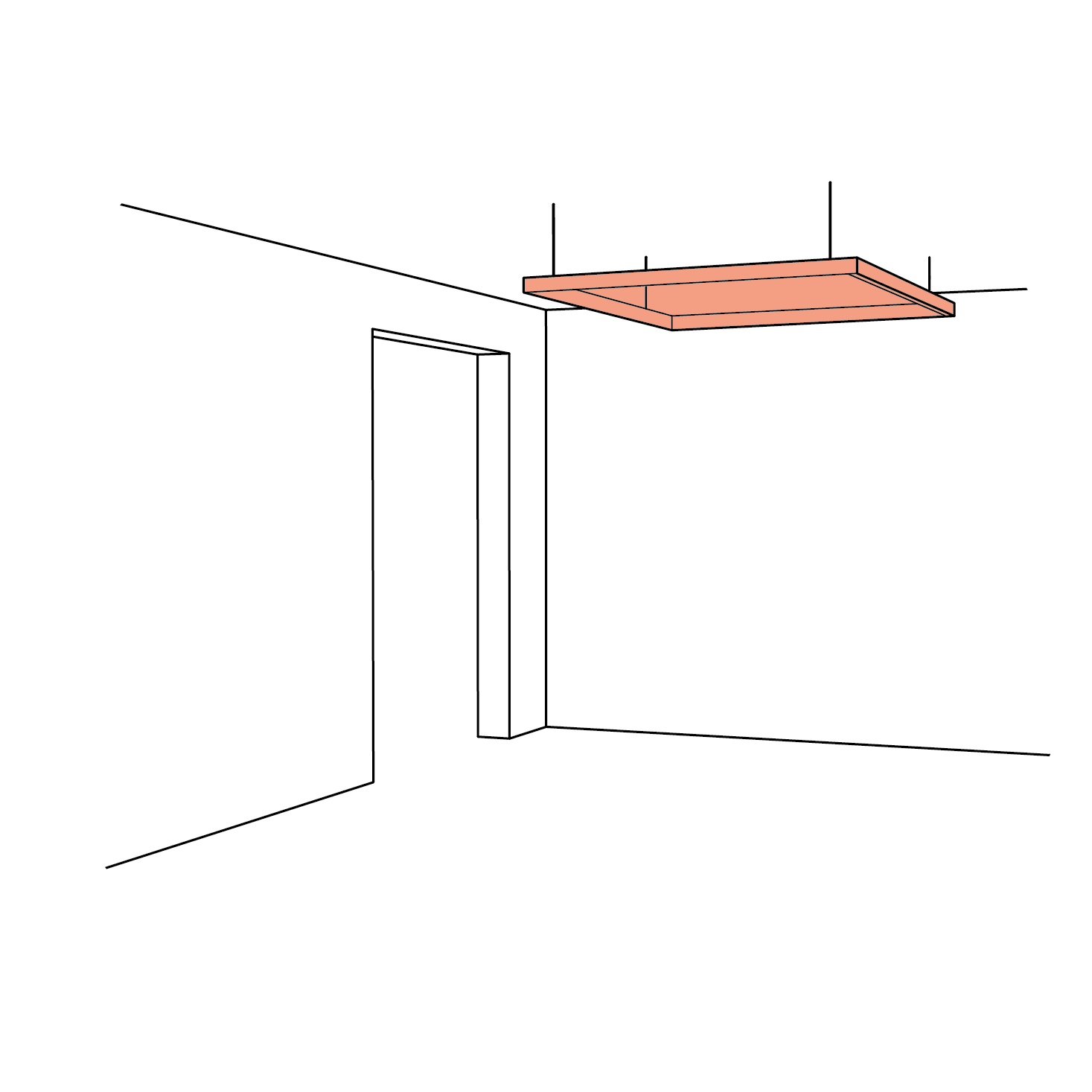

How do I get my products installed?

Joiners and upholsterers are the best skilled to install our products easily. We work regularly with some professionals, who we can recommend. If you have a tradesperson, who you trust, we can support him/her. You can find our installation instructions and tips here.

Got a technical question?

All our technical data sheets are here. Your regional Texaa business representative can also help; please feel free to contact him/her.

Can I have an appointment?

Our business representatives travel every day to installation sites and to see our customers. Please feel free to contact them and suggest the best dates and times for you, preferably by e-mail.

Lead times

Our products are manufactured to order. Our standard manufacturing time is 3 weeks for most of our products. Non-standard products take from 5 weeks. We also perform miracles on a regular basis! Please feel free to contact us.

Who should I call?

To get a quote, a delivery time or technical information, we recommend you call your regional Texaa business representative, who you can find here.

Order tracking

If you need information about your order, please contact the person in charge of handling it: the name is at the top left of your quote.